It’s a New Year, and as winter turns to spring, with warmer days and longer periods of daylight, mother nature prepares for migration. But nature is not the only one looking to migrate. 2025 sees the end of support for Microsoft Windows 10 and so organizations need to also prepare for the migration to the Windows operating system too.

It doesn’t seem all that long ago that we would have been having similar conversations regarding Windows 7 which is a fair few years ago now, back in January 2020. Can you believe that it is almost 11 years since the end of life of Windows XP back in April 2014.

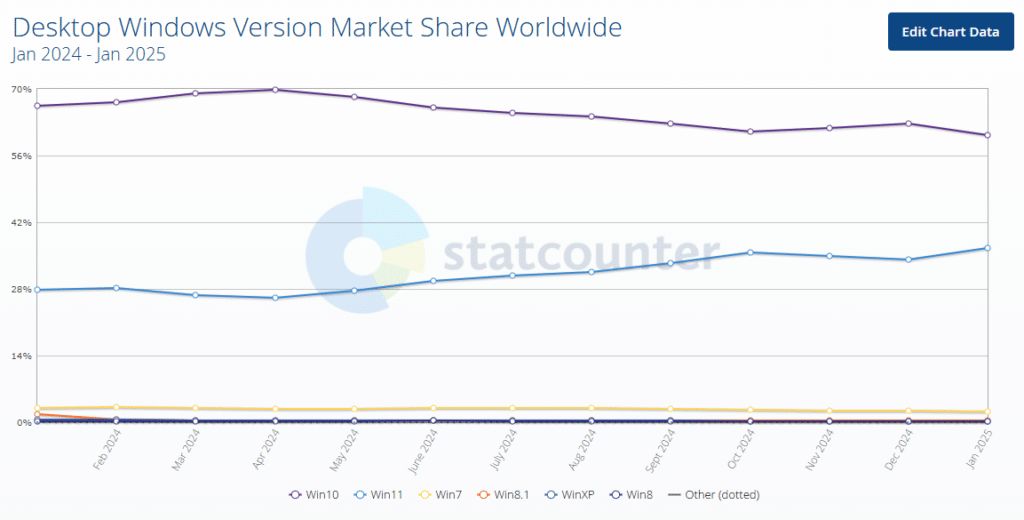

Even though 11 years have passed, 0.3% of the global desktop market are still running Windows XP, and almost 3% are still running Windows 7. Given that Windows 11 launched back in October 2021 you would think that most organizations would have migrated already, however, in reality that is not the case. Statcounter shows that just over 36% of the global Windows desktop market is running Windows 11, while Windows 10 still remains at a touch over 60%!

That means that 60% of the global desktop market customers have just over 8 months to plan and execute their migration to Windows 11.

Extended Support: A Costly Temporary Solution

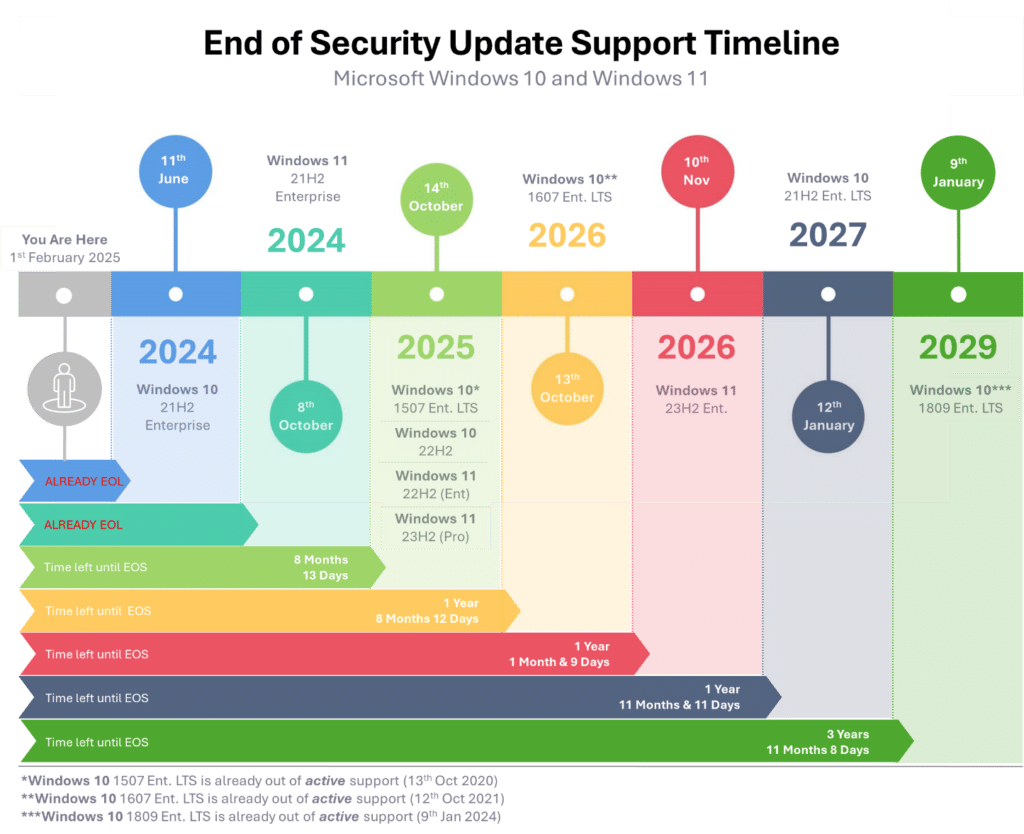

One other thing to be aware of, and that’s not meant to scare you even more, is that early versions of Windows 11 have already gone to the end of support. Windows 11, 21H2 (Home, Pro, and Pro Education), has already gone end-of-life, and Windows 11, 21H2 Enterprise went end-of-life in October 2024. Two more Windows 11 versions share an end of support date with the final version of Windows 10, in October 2025.

There is of course the option of a life raft in the form of extended support. But this is not a fix, merely a play for more time. And one that also has a cost attached to it the longer you try to stay afloat in that raft.

In that respect extended security support should be seen as a “last chance saloon” option for those who can’t migrate yet, not as an option to extend the lifecycle of the existing Windows estate.

If you are unfamiliar with the extended support option, then it is worth quickly highlighting the difference between active support and security support. With active support, you still receive updates that may include new features plus any fixes, etc. Security support is precisely that. You will only receive critical security patches and updates and no new features.

The Cost of Delaying Windows 11 Migration

Going back to the subject of costs, what do those numbers look like?

For standard customers, the cost of receiving extended security updates is $61 USD (approximately £50 GBP) per device for the first year. If you want to extend it for a further year, then the cost of that second year doubles to $122 (£100) per device. Finally, a third and final year can be purchased, where the price doubles to $244 (£200) per device.

If you use Microsoft’s cloud-based update management tool, Intune, a discounted option is available. This reduces the year one cost to $45 per device, the year two cost to $90 per device, and finally, the year three cost to $180 per device.

We have so far mentioned standard customers. However, there is an exception to the pricing rule when it comes to educating customers. For education customers, the cost of ESU for year one is $1 per device, year two is $2 per device, and finally, year three is $4 per device.

To put this into perspective, let’s take an example of a customer with 1,000 devices running Windows 10. Maintaining ESU for the first year will cost $61k, $122k for year two, and $244k for year three. Those figures are by no means a drop in the ocean, but you need to weigh up the cost of remaining secure while you migrate if it will take you beyond the end-of-life dates.

There is one other key point to highlight. If you decide not to take ESU in the first year and then decide that you do need ESU in the second year, you will still have to pay for year one and year 2, meaning the cost per device is $183.

So, What’s Next?

The obvious answer is to migrate to a supported version of Windows 11. But is it that as straightforward as it sounds? Most likely not. If you haven’t already started your planning and testing it is unlikely that you will get migrated by October.

Understanding the Need for Migration

Migrating to a new operating system is a significant undertaking that requires careful consideration and planning. With the end of support for Windows 10 approaching, businesses must migrate to Windows 11 to ensure continued security, compatibility, and support.

A successful migration requires a thorough understanding of the need for migration, including the benefits of upgrading to a new operating system, the risks of delaying migration, and the potential impact on business operations.

Understanding your application compatibility landscape

First and foremost, will your applications work or be supported on a new operating system? Understanding the application landscape is key. For example, are there any apps that are no longer used? Do you have multiple versions of the same application?

You need to build an end-to-end picture of your applications so you can confidently answer how many apps you have. I would put money on the fact that the answer will be way higher than you think.

Ensuring application compatibility is crucial when migrating to Windows 11, as core business applications must function properly to avoid disruptions.

The likelihood is that apps would continue to run if they were running on Windows 10, but you still need to test them on the new OS just in case. These can all be tested as you build your new OS image.

If you’re running older apps on an even older OS that are equally as business critical, you can look at alternative ways of delivering them. Maybe deliver them as published or virtual apps or maybe containerize them.

Pre-Migration Planning and Preparation

Pre-migration planning and preparation are critical steps in ensuring a smooth transition to a new operating system. This includes assessing the current IT infrastructure, identifying potential compatibility issues, and developing a comprehensive migration plan.

IT leaders must also consider the time and resources required for the migration process, including testing, training, and deployment. A well-planned migration can help minimize disruption, reduce downtime, and ensure a successful transition to the new operating system.

What About the New Hardware?

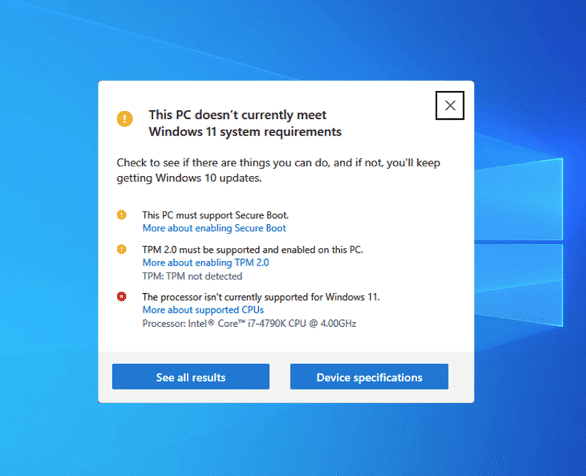

We’ve talked about apps, but equally important is the hardware. To support Windows 11, organizations may need to consider procuring new hardware to avoid conflicts during the transition.

Having assessed your hardware estate, you’ll understand whether your current devices will or will not support Windows 11. For the basics, Windows 11 requires the following configuration:

- 1GHz 64-bit CPU with two or more cores

- 4GB memory

- 64GB hard disk space

- UEFI Secure boot functionality

- Trusted Platform Module (TPM) 2.0. You can now install with TPM 1.2, but it’s not officially supported

- DirectX 12 or later + Windows Display Driver Model (WDDM) 2.0

- HD Display (720p) greater than 9” and 8-bits per colour channel

Overall, the hardware requirements don’t seem too onerous, and the vast majority of endpoint devices will likely be able to run Windows 11 comfortably. However, before we get to two areas that might be an issue, there are a few things to call out.

One thing to be aware of is that these are the minimum specifications to run the Windows 11 operating system. I don’t want to state the obvious, but these specs are just for the OS and don’t consider any application resource requirements. Applications may need more CPU and memory resources and potentially more storage space.

Depending on the type of application, the graphics requirements might be greater, too. It’s worth running some benchmark performance tests on any hardware that’s being upgraded.

Anyway, back to those two potential showstoppers: TPM and CPU generation.

First off, to install Windows 11, the endpoint device must have a TPM 2.0 chip. As you can see from the screenshot above, Previously Windows 11 would not install without it, however Microsoft have relaxed this slightly and you can now perform a fresh install with TPM 1.2, however it is not officially supported.

Depending on the age of your hardware, this may not be a showstopper at all, as the device may have a TPM module, given that TPM 2.0 was introduced back in 2014. However, having said that it doesn’t mean your hardware vendor fitted it. But if you don’t have it, it could stop your migration in its tracks unless you swap out the hardware.

In Windows 11, the TPM is used for things such as Windows Hello and BitLocker. It may well be that your hardware has the TPM module present (your assessment data will tell you that), but it’s currently disabled, which would require a change of BIOS settings to enable it. Something you need to factor into the migration process.

As a side note, this is also true for the Windows Server 2022 operating system. In the case of server hardware such as Dell, the TPM module is typically not included as a standard and will need to be added as a plug-in module to the motherboard.

The other potential showstopper, again highlighted in the screenshot, is the CPU. While your current CPU may easily meet and exceed the required clock speed and core count, this isn’t the only requirement you must be aware of.

The CPU generation, or how old it is, also comes into play and might be a bigger issue as Microsoft supports the Intel Generation 8 and newer CPUs and the AMD 2nd Generation Ryzen CPUs and newer, both of which were only released in 2018. A mere six years ago! Four years after the introduction of TPM 2.0. Given that fact, it’s possibly more likely that you have an unsupported CPU rather than a missing TPM. Your assessment data will tell you what CPUs you have out there.

You can check your results against the Windows 11 supported Intel CPU page and the Windows 11 supported AMD CPU page.

What’s Next for a Smooth Transition?

Migrate is what’s next. It’s the only real option when running desktops and laptops. Not migrating to Windows 11 will mean that you’ll be running an unsupported operating system and all the risks of doing that.

The main one is running an operating system that is vulnerable to attack. Considering the convenience, you might opt for an in place upgrade or in place upgrades to maintain existing settings and data.

In terms of approach, you should first run an assessment to understand what you have deployed currently. That will give you the number of devices under the spotlight that need the operating system updated and the applications being used.

This will enable you to scope the size of the migration project to help determine timelines and budgets. Many businesses rely on experienced partners to manage these complexities and ensure a smooth transition.

Timelines are key too. If you need to extend support in order to complete migration and continue with a supported environment, from a security perspective, you could upgrade to Windows 10 1809 LTS version if you haven’t already. That means you’ll receive security patches until January 2029. Effective user training during this process is essential to ensure users feel supported and informed.

There are then the alternative options. Now could be the ideal time to migrate to a virtual desktop or virtual application solution either on-premises or from a Desktop-as-a-Service provider.

This would certainly solve your hardware question to a certain degree, however if you continue to access virtual environments from a Windows device you will still need to have an updated and supported OS, but maybe these devices could be repurposed into a thin client device using something like IGEL OS.

When considering a major Windows update, it’s important to evaluate different installation methods, such as clean installs versus in-place upgrades, to ensure systems function properly and mitigate potential technical issues.

In summary, given the options outlined above, the one thing that is not an option is to do nothing.